- Call 908 543 4390

- Email

- Dr.Joni Redlich PT,DPT

Savvy parents know that every child has their own sensory preferences and things they avoid. Whether it is picky eating, not liking the seams in socks, or having a hard time sitting still because the child’s body has the wiggles, every child has their own sensory world. Every adult has their sensory preferences too, but we learn to manage our needs by taking walks when we need to wake up a bit, chewing gum to stay focussed, or shaking our foot while listening to a speech.

Every child will have their own personal sensory profile, but when is it time to get help. When sensory preferences are impacting daily life, that’s a good time to seek help from an occupational therapist or a physical therapist.

Below we’re going to introduce the difference sensory systems and give you some tips to start figuring out what sensory strategies will help your child.

Kids who seek out rough play, jumping and/or crashing, or our kids who like to lie down on the ground a lot may need more input to this system. It helps us to sense movement and organizes our bodies to help with coordination, body awareness and spatial awareness.

TRY activities that involve:

Kids who appear to seek constant movement, are risk takers and like to be upside down may need more input to this system. Some kids may look more sedentary or lethargic and may also need some vestibular activation! This is another movement sense, it is related to our head position in space, and gives our bodies information about balance and is closely related to our visual system.

TRY activities that involve:

Kids who are constantly touching and fidgeting may need more input in this area. Kids who are extra sensitive to seams or clothing, or avoid getting messy might be on the opposite side of tactile processing. It refers to our sense of touch, and can impact all areas of function from eating to walking to feeling the nuances of toys and materials during self-care and play.

TRY activities that involve:

Kids who are constantly humming, yelling, and making other noises, they may need more auditory input than other children. Kids who zone out, seem to ignore you, or struggle to shift from one listening to another listening cue/instruction (or for example, respond to their name).

TRY activities that involve:

Kids who require more visual input may look closely at objects. They may seek out moving or spinning objects. They may have difficulty focusing on information presented visually. On the other end, lights might be too bright or the child may struggle to adjust to lighting changes, or become overwhelmed incertain lighting, like fluorescents.

TRY activities that involve:

Kids seeking out input to these systems may lick or smell objects like crayons or toys. Chewing also provides proprioceptive input, so kids may bite or chew on objects (think pencils or shirt collars). May be averse to tastes or smell, picky eaters tend to be sensitive in this area.

Links to some of our favorite sensory products:

Need some more help finding sensory savvy solutions for your child! Reach out to us at info@kidpt.com and schedule a FREE Discovery Visit with one of our therapists to learn more.

When learning about any topic, you can only learn so much from studying the academic literature. For example, if I want to understand Italy I can only learn so much from a textbook. In order to truly better understand Italy, It is vital that I actually go to Italy and experience first hand the climate, the weather, the people, the food, and the culture in varied settings and at different times of the year. Some things can’t be taught, they need to be experienced.

Why don’t we also do this with people with special needs and specifically autistic individuals?

We may learn the physiology, the outward signs and symptoms, and theories on how to address and “treat” autistic people, but we will never truly understand autism by only relying on an outsider’s perspective. It is vital to listen to autistic voices in order to better understand, support them, and create an inclusive environment.

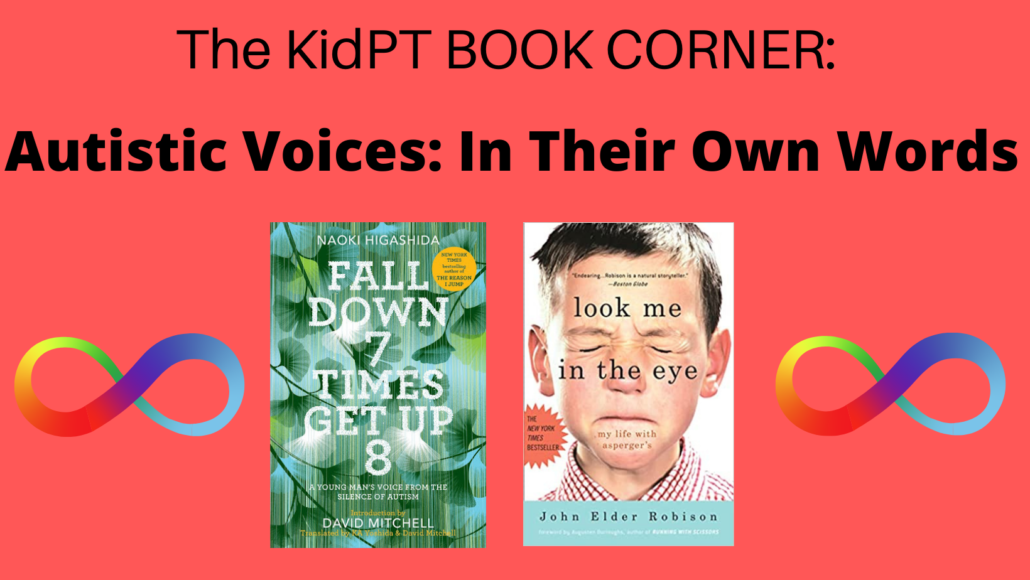

As autism is a spectrum and no two autistic people are the same, it is important to experience the perspective of a variety of people; from those who are non-verbal to those who have more asperger-like symptoms, those who have more physical limitations to those with more cognitive impairments, and from the young to the old. With that in mind, we will be discussing two books: “Fall Down 7 Times and Get up 8” by Naoki Higashida and “Look Me in the Eye: My life with Asperger’s” by John Elder Robison.

Naoki Higashida wrote the book “The Reason I jump” at age 13 which has been translated from Japanese to over 30 languages. Through his works he has provided the world with the inner voice of a nonverbal child and now adult with severe autism. “Fall Down 7 Times, and Get Up 8” is an incredible book in which he shares wise insight, in depth descriptions of his thought processes, and also clever, creative writing. Naoki has a refreshing and enlightened outlook on life and his autistic diagnosis. He covers topics ranging from inexpressible gratitude for his family to the thought processes he uses to register what the sound of rain means to empathizing with his grandfather’s dementia. Despite the obstacles he faces as a nonverbal autistic individual, Naoki is determined to live with purpose and self love.

John Elder Robison is an autistic man born in the late 1950’s who was undiagnosed until much later in life. His book is a captivating memoir of his extraordinary life as he makes it to the big time in the music industry, the corporate world, and then owning his own car service and dealership company while finding his niche in the world as a neurodiverse individual. He discusses the challenges of not knowing why he was different from other people and repeatedly claims that his childhood and early adulthood would have benefitted from a knowledge of his diagnosis.

3 Takeaways from Both Books:

Autistics prefer to be alone: Debunked

Although it is a common trend for those with autism to isolate, that is more of a response to frustration than a desire to be alone. We all have experienced the pain of not fitting in and feeling uncomfortable in our skin and how all we wanted to do in that moment was run away. Those with autism, in self-preservation can do the same. The heart-breaking reality is that neurotypical people often grow out of this phase as they have more social tools available to them, while those on the autism spectrum, if not properly socialized and made welcome in a community, can find themselves isolated. Communication is a tool most people take for granted and underestimate. At the deepest levels of who we are, we crave to be known and to know others. It really is what life is about and autistic people are no exception. Communication is what makes that possible. John Elder says that he can’t speak for other autistics, but that he never wanted to be alone. He explains that due to repeated failure with attempts to connect with people, autistics are at risk to turn inwards and withdraw from others. Naoki describes wordlessness as a “soul crushing condition” and the loneliness is agony. But this loneliness can be interrupted as he goes on to explain that “if there is a single person who understands what it’s like for us, that’s solace enough to give us hope.” Naoki describes that just being in the presence of his family brings him comfort. He describes, “and from my face and reactions you wouldn’t know that I’m enjoying myself, but just watching my family being a family brings me great pleasure.”

Autistics want acceptance

Naoki believes that he has his positive outlook on his autism because his parents were neither in denial of his autism or limited his potential because of it. They allowed him to dream, make choices, and respected his feelings. They treated him with the expectation that he was capable of more and provided him with relevant resources. They loved, dreamed with, and accepted him. It is natural to want the best for someone with autism and try to help them or even fix them. Naoki and John Elder agree that the deeper need is not to be fixed, it is to be loved and accepted for who they are, as they are. Naoki said, ““Love and only love makes whole the heart of those made desperate by loneliness.” Naoki’s advice is simple. Do as his parents did: “please lend us that support as we strive to live in society.”

Autism is a communication disorder

Although someone with severe autism may not be able to show typical outward signs of understanding, it does not mean that they do not listen or have an inner voice that wants to communicate. Autism “may look like a severe cognitive impairment” but “it is a sensory processing and communicative impairment.” The old adage, don’t judge a book by its cover, is an important lesson to remember when spending time with someone with autism. Naoki gives us a sober insight that, “we are listening to everyone around us, & we hear you, you know.” He describes how demoralizing it can be when people speak about him as though he is not in the room. Everyone deserves to be treated with respect and dignity.

Likewise, John Elder provides insight into why interactions and conversations with neurotypical people can be challenging and why his responses and actions can often be misinterpreted as socially inappropriate. He has a gifted way of describing his logical thought process which contributes to his difficulty reading social cues, engaging in small talk, and interpreting the intention behind the words of others. He explains that sometimes people have less compassion for him because there is no outward sign of his conversational handicap, but instead see him as arrogant or psychologically unstable. He suggests that with a deeper and broader understanding of the autism spectrum, the general public will be able to create a better and more inclusive environment for the neurodiverse.

To those of you reading this who communicate often with someone with autism, I want to encourage you. Yes, this is difficult, yes we will make mistakes, and yes, at times our frustration can get the best of us. But we need to remember that even if we don’t say or do the right thing all the time, the important thing is we love, respect, and accept autistic people for who they are.

Referenced below are the books covered and others like it.

References:

“Fall Down 7 Times, and Get Up 8.” Naoki Higashida, KA Yoshida, and David Mitchell

“Look Me in the Eye: My Life with Aspergers.” John Elder Robeson’s Book,

Further Reading:

“The Reason I Jump.” Naoki Higashida, David Mitchell, and Keiko Yoshida

“Carly’s Voice: Breaking through Autism.” Arthur and Carly Fleischmann

“How Can I talk if My Lips Don’t Move? Inside My Autistic Mind.” Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyay

“Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant.” Daniel Tammer

“Pretending to be Normal: Living with Asperger’s Syndrome.” Liane Holliday Willey

“Thinking in Pictures.” Temple Grandin

What does movement have to do with Autism, you ask? In short, EVERYTHING! Movement is the way we interact with our environment, one of the ways we make sense of all the information around us, and the way we turn our will into action! Even something that seems so based in the brain, like writing or typing our thoughts down, involves movement to actually get those thoughts onto paper or into a computer.

But what if the wiring in your brain telling your body to move a certain way wasn’t communicating that information effectively?

Or what if the information you were getting from your environment, like the sights or feelings around you were coming in as too bright, too sharp, or not clear enough?

What if you couldn’t necessarily tell where your body was in relation to your environment or where your legs and arms were while walking around?

It would be so much harder for you to get around without knocking into things, to react to your environment in the safest way, move the way you wanted, and keep your stress level down while doing all of these things, right?!

These are just some of the small or large mountains that a person with Autism needs to climb on a daily basis to feel like their normal selves and to engage with our crazy world. Movement can be overwhelming and difficult to coordinate or extra movements may be necessary to feel where their bodies are in space. With the many lenses we can look through from a therapy perspective, we often land on the tie between Autism and movement and want to discuss the connection and why children with Autism may be inclined to move more and to move in their own individual way.

These are just some of the small or large mountains that a person with Autism needs to climb on a daily basis to feel like their normal selves and to engage with our crazy world. Movement can be overwhelming and difficult to coordinate or extra movements may be necessary to feel where their bodies are in space. With the many lenses we can look through from a therapy perspective, we often land on the tie between Autism and movement and want to discuss the connection and why children with Autism may be inclined to move more and to move in their own individual way.

Movement to meet sensory needs:

Movement that is Difficult to Coordinate:

Now add extra distractions of daily life to the Mix!

These are just some of the big reasons why movement can be tricky and discoordinated in autistic children and how it can impact os many areas of daily life, from getting dressed in the morning to social interaction. We know this is A LOT of information to take in, but this connection is an important one to make because when movement is hard, it makes coping with everyday life hard and stressful! If you feel like coordinating movement or movement with other daily tasks is sometimes tricky for your child, call (908) 543-4390 or visit our website at www.kidpt.com to schedule a FREE Discovery Visit today!

Extra reads: